The Coffee Roasting Process: What Roasting Actually Does To Coffee Beans

- Why we even roast coffee in the first place

- How big roasting machines are better than other industrial kitchen gear

- What’s going on inside the bean at different stages

- And how those stages affect the final flavor

This blog will give you an idea of how roasting here at Driven is a craft, not a factory production line. It’ll help you understand how flavors are formed and help you pick better beans next time you’re trying to decide between a few bags. Let’s jump in at the beginning.

Why We Have To Roast Coffee Beans

Coffee beans, as you know, are actually the seeds of a small cherry-like fruit. When they’re first harvested and removed from the cherries, they’re hard, dense, and a green color. If you were to try to brew these green coffee beans like roasted coffee, the result would be unrecognizable—and gross. Before they’re roasted, coffee beans taste very vegetable-y and “green”. They’re also so dense that most grinders wouldn’t be able to break them down into smaller pieces. Not really good for brewing coffee. Coffee roasting breaks down the bean cell structures and pulls out the moisture in them so that they can be ground. Roasting also initiates a bunch of complex chemical reactions that create the rich flavors we love in coffee, whether its fruity and floral notes or deeper chocolate and caramel tones.

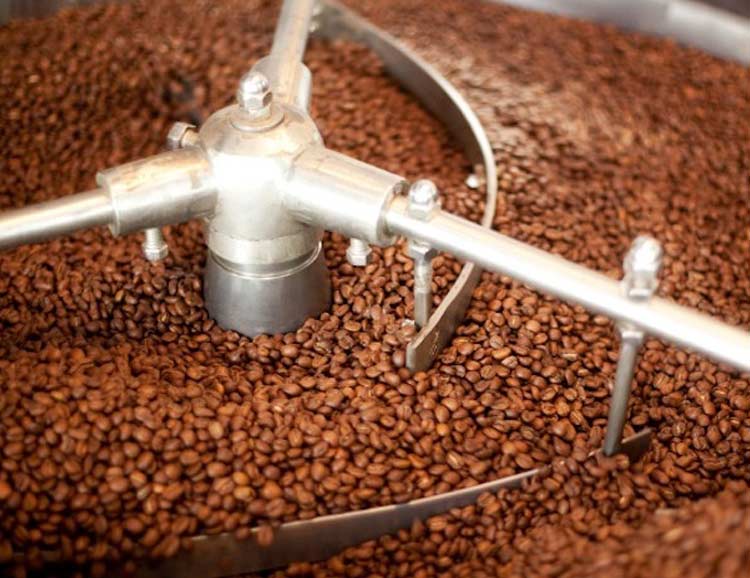

Why We Use Big Coffee Roasters

Here’s the thing: it’s possible to roast coffee in a skillet, over a fire, or in an oven. In fact, it’s been done those ways for hundreds of years. However, these methods fall short in some dramatic ways—and the consequence is unpleasant, unbalanced flavor. The biggest weakness of these methods is the lack of control. Roasting specialty coffee generally requires a pretty specific temperature increase throughout the entire process. There’s wiggle-room for different techniques and styles, but on the micro-level. Skillets and ovens cannot enable this level of control or precision. Another drawback of these methods is the fact that they cannot roast beans evenly. Skillets are hot, but the air around them isn’t. Baking distributes heat a little more evenly, but you can’t stir the beans without dropping the temperature. Unevenly roasted beans are not tasty beans. Big commercial roasters continually toss the beans to ensure they’re all roasted evenly. They also give us a very high degree of control over the temperature. For delicious specialty coffee, they’re the way to go.

5 Main Chemical Reactions Inside The Beans

There are thousands of chemical reactions that take place during coffee roasting, but we’re just going to focus on the five big ones and how they develop the coffee’s unique flavors. For the first several minutes of roasting, the beans are heating up, actually expanding in size, becoming a yellow-tan color, and starting to smell like toast or popcorn. And then comes the good stuff.- Maillard Reactions — This is a big one that’s responsible for a large portion of roasted coffee flavor. Between 300 and 400 degrees Fahrenheit, a variety of chemical compounds, including amino acids in proteins, start reacting together to create more tasty flavor and aroma compounds. Hundreds of flavors are developed during this stage in just minutes.

- Caramelization — Around 370 degrees, the natural sucrose (sugars) in the beans start to caramelize. Aromatic and acidic compounds are released into the bean, and that sweetness goes from being similar to refined sugar to a more deep, satisfying honey or caramel sweetness.

- First Crack — Just above 400 degrees, remaining water in the bean vaporizes, causing the bean to expand and crack audibly. The beans lose about 5% of their weight from water-loss and turn a light brown color. Shortly after first crack is where light roasts are removed from the roaster and cooled.

- Pyrolysis — Close to 430 degrees, the beans experience another chemical change that rapidly expels carbon dioxide trapped within. The beans turn a darker brown color and lose around 13% of their weight from the lost carbon dioxide. During this time, the bright acids from caramelization are being smoothed out from the deeper roast and more rounded flavors are forming.

- Second Crack — Just before 450 degrees, the beans experience a second audible crack, largely from the pyrolysis forcing out carbon dioxide very quickly. Just after this point, the sugars and acids begin to break down into the darker woody, carbon-y flavors that are more common among dark roasts and the classic dark roast coffee aroma becomes fully developed.